High Rise /–>/ Ruin Value

April 2nd, 2016

Mister Attack: So, Illogical Volume and I concur that High-Rise was excellent. I have to confess to not being familiar with Ballard or Wheatley, but this was pretty much up my alley. (As someone currently spending far too much time painting up a flat of his own, and discovering more and more problems, I can relate. Well, that and living in a classist nightmare of horrible bastards with ‘good’ intentions).

It took me a while to unpack that the satire is at once broad as fuck, but has these layers. It’d be fair to say I was not all in the building at work on Friday, I was off in Royal’s tower. Every bit points to something, although perhaps some of that was the damaged foundations I brought into the cinema with me. Sometimes it’s subtle, as with our protagonist’s namesake not being immediately to hand, and with others it’s screaming from the rafters.

There’s this British sitcom going very wrong feel – like someone should be watching this in the background of The Filth. A comedy of manners, except the manners devolve to the best way to lie in wait to bludgeon the neighbours. Hiddleston plays straight man to a mix of sitcom and soap opera grotesques, trying to act like all this is normal, with his own mania creeping around. A hollow man with a shallow inner life he’s trying to create for real. Except, well, he’s not that straight. Illogical Volume mentioned Brazil as another touching point. He’s not wrong. The conflict of hierarchies and shallow men trying to fill the void with what they think they need is the same, but the farce is played straighter, less panto. The difference is manifest in the likes of Bob Hoskins yelling about tampered ducts for the benefit cheap seats, versus Reece Sheersmith tetchily complaining that people aren’t following the rules about the bin chutes. That said, both movies feature protagonists who are at odds with their surroundings, but Hiddleston’s Laing embraces the new paradigm, whereas Pryce’s Lowry is engaged in defiance by ineffectual escapism.

At the time, we immediately talked about the Garland/Travis Dredd, due to some of the establishing shots, I mentioned World On A Wire as a similar 70’s futurist meltdown, although mostly tonally opposite. At some points High-Rise’s camerawork emphasises a static, clinical detachment, and at others a drunken wooziness that compliments the mental state of the characters. Same with the soundtrack, which is more of an audio landscape to compliment the location. Laing’s poise is only a surface.

Illogical Volume: I keep thinking about High Rise and Dredd. It’s an obvious comparison, maybe – as you say, it’s there in all the establishing shots – but also a strangely inappropriate one on some levels. We’re dealing with the wrong sort of carnivalesque here, I think, and that makes me wonder: what would it take to establish these soap opera grotesques in a stern action movie context?

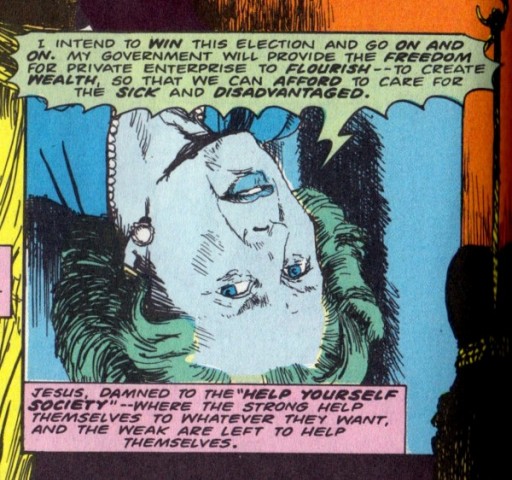

Maybe an unsubtle political joke? One you might find in a narky, anti-authoritarian kids comic? One that might work better in 2000AD than it does in a J.G. Ballard adaptation?

Enter the voice of Lady Thatcher, invoked by an unfussed child who has spent the whole movie straining to glimpse the future through the carnage, those withering tones broadcasting over a makeshift radio, talking about market capitalism and the triumph of individual freedom:

Well, okay, that’s from Hellblazer #3 by John Ridgway and Jamie Delano, but you get the idea.

Mister Attack: Unsurprisingly, the Thatcher/tower block connection is quite immediately affecting to me.

(it did also take me back to my postman days. There’s this building full of the well to do up near part of the canal that has a pool in one of the basements. Place stank of chlorine at the lower levels).

I grew up in a council estate with four towers looming over the tenements. When she ushered in the right to buy, there was, as near as I can tell, a fair amount of uptake. However, it seems you can’t get a mortgage for a tower block, so, as I recently learned when a couple went up for sale, it’s a cash only purchase. The tower blocks seem to make up the majority of the social housing in the area. Have had loads of arguments over the years with my parents about how unfair it is that people they know are squashed into those flats, and how the older children are having trouble getting council houses, yet obviously they, my folks, bought their flat yonks ago and contributed to the situation. Whenever I stay at my folks, I miss the fact that the tower near us used to have a partially open ground floor. Bits that now have wee function rooms where the locals have meetings and activities used to be open to the elements. The wind would howl through the columns, and nothing made my bed seem more comfortable and snug than letting that noise lull me to sleep.

Illogical Volume: Well, you know me: I’m the guy who did (is still doing?) the comics zine about social housing, high rise flats, and this mess we’re in. It’s my day job, explaining to people how the Right-to-Buy bought enough good will to pay for the death of social housing in the UK, to try to help people living in the flux of it. That stuff was always going to be on my mind while I was watching the movie.

How could it not be when, on some level, it is my mind?

[/MINDLESS SELF PROMOTION]

Which is interesting, actually, because this is probably the level on which Wheatley’s adaptation is most faithful to Ballard’s novel: it has almost nothing to do with that, being more concerned with a metaphorical representation of modern living than any sort of survey of what’s been done to the poor.

Mister Attack: I kept meaning to ask you at the time, but it was on my mind about how Laing was probably named as a dig at the psychologist of the same name. I take it you knew that going in?

Illogical Volume: Aye, and I sat there throughout the whole movie basking in a totally unjustified smugness because of it.

Mister Attack: See, I kept forgetting to ask, then I started to think about why the hell I knew his name. I was pretty sure it wasn’t my failed A-Level from 1998. A quick look at Google reminded me he was covered in Adam Curtis’ The Trap: Whatever Happened To Our Dream Of Freedom. Curtis is another one for the grand flourish and getting his point across with maximum disregard for subtlety.

I’m nowhere near educated on the subject enough to talk about Albert Speer, but I did think of that idea of Jeremy Iron’s architect, Royal, as a First Architect figure. The brief reading I did yesterday did introduce me to his idea of leaving work that awed the future from the state of it’s eventual collapse. Royal’s great hand reaching out from the dust, like a diseased claw.

Illogical Volume: It strikes me that Royal’s work isn’t so much supposed to awe the world outside of it as change the world within.

In the source novel, Ballard collapses Royal’s vision of building as crucible into Laing’s professional purview: social space blurs into inner space, and is transformed into a strange parody of the workings of the mind // a testament to its capacity for destruction.

Wheatley, Jump, Hiddleston and co perform a series of demolitions on Ballard’s vision, all of which are more effectively executed than certain real world efforts in my neck of the woods have been – if less slick than others. They collapse the rabid intellectualism of the book into something far grubbier, a lower order of unreality, one full of League of Gentleman-esque grotesques, slow motion dance scenes, and moments where it seems that the audience may yet dream their way into a Benny Hill sketch. Some viewers have been repelled by the film’s deliberatelydated bacchanalia, but this sort of discord is Wheatley and Jump’s speciality.

I’ve not seen Down Terrace but Kill List, Sightseers and A Field In England are equal parts mystical England and mysteriously persistent bowel complaint, and so it proves with the urban alienation of High Rise. The big ideas are still there, in other words, communicated in the Gilliam-edged simulation of period details, in matter of fact dialogue that matches Portishead’s cover of Abba’s ‘SOS’ for manic joylessness, and in cuts that don’t so much jump as flicker (like failing lights // firing neurons?).

Why, then, does the movie need to underline its demonstration of the way grand modernizing plans and atomized/liberated living condition can act as multipliers of brutality by gazing out at the audience and saying “A bit like Thatcher, innit?”

These flaws are built into the foundation of the work, in the occasional Watchmen-esque dialogue that doesn’t so much ask as demand that the viewer see double – Laing is “finished” at the start of the movie, and concludes it by explaining that he has been talking “to the building” in case you hadn’t realized that you were already living there. Like the final flourish, these elements feel like they belong in other modes/media. To keen to make a case for their cleverness, they somehow make the film feel trashier than it otherwise might, opening up the path to Dredd ramping in on his Lawmaster, or the Attack the Block crew stepping up to defend the whole mess from getting even worse.

These are the only things that you can build on these shaky foundations: enjoyment of a lightly ironized authoritarianism, or the thrill of finding a sort of desperate camaraderie in the ruins. I’ve thrilled at less before and will again, but honestly, it’s not enough and you know it.

If High Rise has any true value it’s in reigniting the urge to rip it up and start again.

Mister Attack: Possibly because High-Rise is about upper class versus middle class battling for supremacy? Working classes need not apply. This hermetic bubble purports to be about new structures, but only people of a certain class and race count, I guess. Similarly, Hiddleston’s Laing has no family anymore. No attachments. His acceptance of the structure is embracing that, to quote Curtis “…out of this struggle came a stability and society, but a bleak and limited existence…” There’s contradiction in that he knows the functions of the brain, but not people. He and Royal are structuralists, baffled and detached from their loved ones.

Illogical Volume: In the end, this is one program of urban regeneration I can actually get behind. Better to demolish High Rise than to continue to live in it, and even if I don’t want to pretend that my aesthetic critiques – critiques of weaknesses so tantalising that I could fill them with fan fiction, small textual insecurities that show me the ways I find to survive here a little too clearly – are a substitute for new social thinking, this combative mode is more promising than Laing’s sense of equilibrium in chaos.

Look outside: the future’s already here // already ruined. What are you going to do with it?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.