Cerebus

May 6th, 2014

The problem with Cerebus is that it’s simply the wrong place to start. You throw people in with this as the starter and they’ll immediately turn away. It’s the work of an amateur, someone who was trying to break into the comics field, and who initially had no plan at all. Where the other Cerebus phonebooks are telling a coherent story, this one is a collection of snippets which only start to cohere into a proper story towards the end.

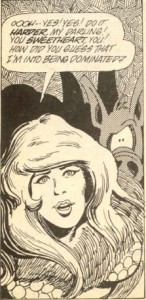

We do need to talk about Sim’s “anti-feminism” at some point, of course. Suffice to say, in these early stories, we don’t get much in the way of a hint of what is to come. We have neither the craft that is to follow, nor the disgusting views that were to turn Sim from hero of the alternative comics set to the pariah he became. You can, of course, see things in there now, looking back. No-one saw them then.

Cerebus, in its first few issues, was designed to do precisely one thing — appeal to the Marvel fanboy. The covers were designed to look just like Marvel covers, and the comics themselves were conscious imitations of Barry Windsor-Smith’s Conan, but with a Howard the Duck style funny animal protagonist. This was not meant to be an innovative comic — Sim thought it might last three issues and be able to get him some real work, by which he meant, yes, Marvel.

Even this early, we can see that Dave Sim is a man who is fundamentally not happy in his time. While the comic was as modern as it could be — perfectly fitting in with the Marvel comics of 1978 — his humour was that of an earlier time. Throughout Cerebus Sim would hark back to 1930s comedy, and that started early on, with Elrod — a parody of Elric who talked like Foghorn Leghorn, and who was Sim’s first truly inspired creation.

The only reason Cerebus had any kind of success is because Sim got in at the start of the direct market, when the comics industry was small enough that there were people who bought literally every comic that came out. At the time there were no real independent comic creators — there were the underground people, but they weren’t selling through the same shops as Marvel and DC. Only Cerebus and Elfquest were selling to the people who were buying Marvel.

While Sim later became an advocate of self-publishing, Aardvark-Vanaheim Publications was managed at first by Deni Loubert, Sim’s girlfriend (later wife), who also accidentally came up with the title of the comic, a misspelling of Cerberus. Loubert’s brother, Michael, came up with the map of Cerebus’ world that was printed in the back of early issues, and invented most of the place names. While Sim was writing, drawing, and lettering the whole comic, he was still reliant on other people.

Reading these early issues, it’s clear that Sim has no idea what kind of comic he wants to do. He jumps about between serious sword-and-sorcery fantasy stories that could be straight out of Robert E Howard and broad farce inspired by Warner Bros cartoons, not with the assured eclecticism that would come later, but with a sense of confusion, like he’s trying to figure out what this Cerebus thing is meant to be. But no matter what, he keeps going.

Cerebus became something of a success relatively quickly, doubling its circulation from the initial 2000-copy print run to 4000 copies by issue eight. It meant that Sim was no longer thinking in terms of getting work with Marvel, but criticising them in his letters page — saying he couldn’t work for them until they became “interested in solid storytelling and parallel development of art and story by the same creator.” How much of that was a pose is hard to say.

We will be talking a lot more about Sim’s attitude to creators’ rights as these essays progress, but it is important to note that Cerebus started out at a time when the Superman film was in preparation, and for the first time the public were becoming aware of just how shabbily Siegel and Shuster had been treated by DC Comics. Being a creator who owned his own work was suddenly something that began to look like a smart business move.

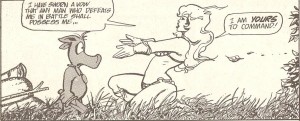

This early on, with little continuity between the issues, the only thing that held the stories together was the presence of recurring characters, mostly parodies of well-known figures from fantasy comics. While Elrod worked well, Red Sophia (a version of Red Sonja who is easy to beat in a fight and a bit of a ditz) was a sad pointer to the future, while Bran Mak Muffin had nothing going for him but the bad pun that was his name.

Then, after issue 11, something happened. Sim “had a nervous breakdown and played bull goose loony in the psychiatric ward of the local hospital for four days”, as he put it in the letters page of issue 12. While he was there, he had what can best be described as a vision. He got the shape of a storyline in his head, one that could take twenty-six years to tell. The story that started in 1977 would finish in 2004.

The story was originally going to be 156 issues, but by issue 14 the comic had gone monthly, and Sim decided to round it off to an even three hundred. As soon as he had his vision, though, the style of the comic started to change, and become more connected. Recurring characters started to interact with each other rather than just reappear as one-off companions for an issue. But Sim’s vision would affect far, far more than just his comic.

Cerebus was the direct inspiration for J. Michael Straczynski when he created Babylon 5, more than a decade later. In particular, Straczynski was inspired by the idea of doing a longform story in a serialised medium, one that had a well-defined end and structure and that lasted a number of years. He used Sim as the example of someone who had managed to do this successfully. Straczynski’s idea has now, of course, become the standard way of doing “cult” TV.

This means that Cerebus may be the most influential comic of its time on today’s culture — everything from Breaking Bad to Hannibal, every current TV show that relies on a planned, multi-season, story arc, is essentially the grandchild of Cerebus — and if Sim had achieved nothing else with his comic, that would in itself be enough to say he was one of the most influential comic creators of his generation. But Sim was improving fast as an artist and writer.

The story quickly moved away from the barbarian millieu in which it started (prompting the first of what would be a regular sight in the comic’s letters page, as people started to complain that it wasn’t like it had been when they started reading) and started to focus on two other subjects — satirising politics in the style of the Duck Soup era Marx Brothers, and parodying superhero comics in the style of Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood’s Mad strip “Superduperman”.

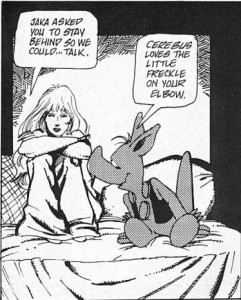

But these parodies hinted at elements of the larger story Sim was working on. Lord Julius may have been just the character of Groucho Marx (Paramount-era Groucho, obviously) dropped into generic medieval fantasy land, but his chaotic methods were those of the Illusionists, a faction that Sim would make one of the major players in his larger storyline. Not only that, but he was also revealed as the uncle of Jaka, a seemingly one-off love interest introduced in issue six.

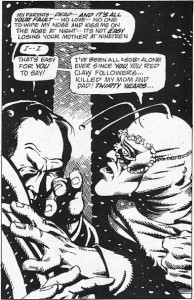

The move to longer-form stories was accompanied by a change in Sim’s art. Rather than the slavish imitation of Barry Windsor-Smith which had been the style of the first few issues, now Sim was allowing himself to be influenced by classic comic artists such as Mort Drucker and Will Eisner, as well as contemporaries like Neal Adams and Frank Miller. The mixture of Drucker’s broad caricature and Eisner’s noirish layouts led Sim to a style unlike any other in comics.

Of course, that style was still that of a young, inexperienced, artist, and in some issues it’s very clear that the strain of writing, pencilling, inking, and lettering a comic every month made Sim cut corners — there are some issues with backgrounds that are mostly shadow — but the growth in his ability over these twenty-five issues is remarkable. It’s hard to believe that the last few issues in this first collection are by the same artist as the early ones.

What had started out as little more than a fanzine had now become a consistently interesting title, and Cerebus was, by late 1980, the most intelligent, witty, comic on the market. And it was about to get a whole lot more interesting. Issue 19 was when, as Sim put it in his annotations for the story, “the story started to get a little weird”, as he started to put the pieces in place for the multiple conspiracies in his plotline.

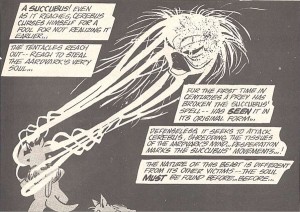

Issue twenty was something wholly different from anything that had come before — a story taking place entirely in Cerebus’ head, while he is in a coma (and communicating telepathically with one character while deep under, and talking to another in periods of lucidity), in which form followed content exactly — each page’s layout made sense on its own terms, but when put together they made one giant image of Cerebus. It’s a bravura piece, something that no-one else would have attempted.

But Cerebus wasn’t an art comic. It was still a funny animal comic aimed at a superhero audience, and with characters like The Cockroach (a superhero who, in this volume, parodies Batman as The Cockroach and Captain America as Captain Cockroach, and who Sim would use for much of the next few decades in various guises) it was closer in appeal to Captain Carrot and his Amazing Zoo Crew than to something like Raw, which started at around this time.

The question was, would the people who were reading the comic to see Elrod, as Bunky the companion of Captain Cockroach, die and become Deadalbino (a parody of the DC Comics character Deadman) — a joke that required a huge amount of knowledge of and investment in superhero comics — want to see Cerebus become something more artistic, and not just the comedy it had been to that point? Given that some were still sore about the barbarian adventures ending, perhaps not.

While Sim was planning the most ambitious Cerebus storyline yet, though, he gave those readers a break, with something filled to the brim with pop-culture references. The last three issues in the Cerebus collection, issues twenty-three to twenty-five, take the basic storyline of Clint Eastwood’s The Beguiling (a wounded soldier behind enemy lines trapped in a girls’ school) and fill it with the kind of spot-the-reference jokes that comic fans loved as much then as now. The headmistress of the

girls’ school is secretly the bald psychic Charles X Claremont, who has made a monster named Woman Thing (who in turn later fights the Sump Thing), while all the enemy soldiers speak like Chico Marx (which is, unsurprisingly, setting things up for the next major storyline). The three issues at the end of the Cerebus collection, then, are comparatively unambitious compared to the issues immediately before them, but they were keeping a continuing narrative going in a way that simply

hadn’t been the case in Cerebus before. Cerebus was now a serial, as opposed to a series, and anyone who had struggled through those early, bitty, stories was now going to get something they hadn’t bargained for. In comics at the time, a three-issue story was a major event . In a world without reprints or trades, you had to keep stories short, so new readers could jump on. The next storyline in Cerebus was going to be twenty-five issues long…

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.