Feeling blue? What else is new?! Have some Comic Reviews & skip the booze!

February 21st, 2015

Multiversity Guidebook #1, by Grant Morrison, Marcus To, Paulo Siqueira and a cast of thousands

This is where I part ways with most of my fellow Mindless: they felt the old thrill while reading the Multiversity Guidebook, with its comic book creation myth and its parade of endless (if by “endless” you mean fifty two) alternative worlds, whereas I mostly just felt exhausted.

It’s a clever mix of marketing material, series bible and actual story, and obvious as it might have been the “dark secret” at the heart of the universe with the Chibi superheroes still reinforced the series’ running theme of how shit it is to be confronted with your own fundamental nature. You could even read the list of junked pitches, elseworlds, prestige comics and parallel worlds that form the centrepiece as a critique, if you were so inclined. As Marc Singer noted in his clipped and clear-headed review of the comic, some of these entries are quietly scathing, and someone with the right (as in “correct”? –Ed) biases could certainly read this endless parade of Batmen and Wonder Women as a critique of capitalism’s frantic grasping (“Empty is thy hand”) and ability to reduce complexity to a series of easily recognisable products.

Is that really enough though? Not for me. The “Guidebook” section of this comic reminded me most of all of Gary R. R. Lactus’ Time of Crowns (with its endless list of medieval clans, “with their tits out”) and the end credits of 22 Jump Street, but it’s neither as succinct as the former nor as merciless as the latter – in the end, it’s just business as usual.

Morrison’s ability to turn product into poetry is well established at this point (sorry haterz), and this strikes me as being as much of a failure of philosophy as it is a lapse of technique. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed pouring over Rian Hughes’ carefully composed map of the multiverse as much as anyone this side of Ben DST, but for me Morrison’s writing has always been at its strongest when it has been liminal and disturbing and free, rather than when it tries to sell you an orderly worldview.

As Geoff Klock argued in How to Read Superhero Comics and Why:

Morrison exploits comic books’ contradictory sixty-year buildup of, and reliance upon, a myriad of metaphysical realms, and brings them al to bear upon a single text, a single site, in a process that I am going to call the dialectic of the sublime. Morrison’s reader, and more importantly his text, is forced into overload by a variety of alpha metaphysics: the vast extremes of outer space, including the realm of Jack Kirby’s New Gods and Wonderworld, heaven and hell, the Still Zone (also called the Ghost Zone and Limbo), the Phantom Zone, Olympus (home of the gods of Greek myth), the fifth dimension, Earth 2 (our antimatter counterpart, which is also separated by a “moral membrane”, i.e. the bad guys always win there), the vanishing point at the end of time (“the atto-second before the last exhausted electron loses its charge to meaningless, unending entropy”, the magic realm of Shazam, the Quintessence, the realm of the Flash’s speed force, the realm of Sandman and the Endless, the land of dreams, and a wide variety of possible and inevitable futures (which, due to time travel, influence the future), ranging from the domination of Darkseid over Earth fifteen years in the future to the 853rd century…

Sandman has as many metaphysical realms as Morrison’s JLA, but they are organized according to a clear hierarchy. Any one of the realms Morrison draws upon could take the top link of the “chain of being”, as it were, but none is allowed primacy. Morrison’s JLA could never be supplemented with the kind of map one might find in an appendix to Dante, for example.

You might not share my taste for run-on sentences, but hopefully you’ll join me in smiling/frowning at that last sentence, which is no longer as true as I might like. The ‘Maps and Legends’ of this issue’s title can be fun, but I prefer Morrison’s comics when they don’t let me feel so comfortable in my understanding, from the clash of styles and stories in Seven Soldiers to the pile-up of baffling revelations in Seaguy and The Filth by way of Doom Patrol‘s many absurd fantasies.

On the other hand, the interaction between Hi-Fi’s colouring and Paulo Siqueira’s line-work during the Kamandi sections of Multiversity: Guidebook suggest a Kirby derived but not overtly Kirby influenced style of fantasy adventure that I could definitely stand to read some more of:

Plenty of space for adventure there, which is the point of this whole exercise, I guess – to keep the punters interested!

Earth 2: The Gathering, by Nicola Scott and James Robinson

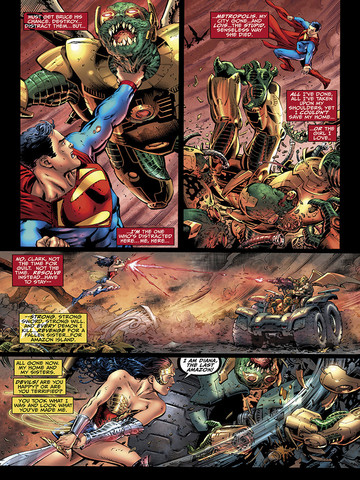

I picked up this book in the library while chasing a similar feeling to the one generated by those Kamandi pics. Like most of the worlds mentioned in the Multiversity Guidebook, it’s populated by alternate version of the DC pantheon, but like the Kamandi section of the Guidebook, it reminded me that I’m not as good as my best tweets when it comes to having The Most Serious Taste In Everything (this is not as surprising as you seem to think – Ed), and that I genuinely do enjoy seeing mostly-recognisable super people struggle to deal with unimaginable pressure:

Nicola Scott’s art isn’t particularly high impact, and it doesn’t provide (or indeed withhold!) enough information to be worth obsessing over, but it does remind me of comics that I have nostalgic associations with, primarily Howard Porter’s busy but still basically comprehensible JLA, with its nervous and untested superheroes and cosmic threats. If Robinson’s storytelling makes me think of comics I enjoyed in the 90s (JLA for sure, but also Waid’s Flash and Robinson’s own Starman) then Scott’s art is crucial to grounding that in felt, bodily experience.

Is this really what I want to aspire to though? Something that reminds me of something I liked before and might therefore conceivably enjoy again, if I put the work in?

Apparently I can’t pretend that I’m immune to the appeal of this stuff, but that doesn’t stop me from wanting more than either Multiversity: Guidebook or Earth 2 have to offer.

Multiversity: Mastermen #1, by Grant Morrison and Jim Lee

Nazi superheroes aren’t that novel either, but surely the moral difficulties inherent in reconciling the horrors of fascism with his pop-transcendentalism would push Morrison into the same form he’s shown recently in Multiversity: The Just and Pax Americana, and in his more recent creator owned work?

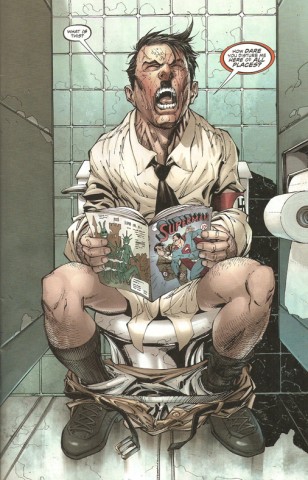

Apparently not:

Of course, as Brother Bobsy pointed out back in the Mindless Ones clubhouse, while Multiversity: Mastermen doesn’t force the reader into a confrontation with their own enjoyment of certain genre tropes by, for example, presenting them with an origin story that involve crescendos of anti-Semitic violence, it still was problematic in other, more subtle ways. The implication that this particular Nazi Superman wouldn’t have let the holocaust happen misses the legitimate point of writing speculatively about the holocaust: that it’s something anyone could have taken part in. The much braver thing to admit would be that the presence of Overman doesn’t guarantee an escape from the quotidian forms of evil that humans are so good at.

I’d use this as a lead-in to an ART PARAGRAPH in which I took a few shots at Jim Lee’s work on this issue, but I’m so late to the game that there’s precious little target left there anymore:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.