Looking Glass Hearts Forever

March 8th, 2011

Being: the long post about Scott Pilgrim that my last two posts were building up to!

So 2010 saw both the death and the rebirth of the comics internet’s favourite slacker hero, Scott Pilgrim. Time to celebrate?

Well, if you ask Brendan McCarthy we should probably just be happy that it’s all over and done with:

I find that ‘comics geek’ bedwetter subculture very inward-looking. It doesn’t interest me at all… Comics like Scott Pilgrim are not on my radar. I think that stuff has already had its day in the sun.

I was going to contest Mr McCarthy’s classification of Scott Pilgrim, but then I watched the movie again and realised that there are two jokes about characters weeing themselves, plus various other references to pee and peeing throughout the film, so maybe he was onto something after all!

Lapses in basic potty training notwithstanding, I still love the comic and the movie, to the extent that I’ve spent the past few weeks immersed in both of them (GEEK!), cataloguing the differences in style and pacing (GEEK!), comparing the three different endings on offer (GEEK!), and listening to commentary tracks (GEEK! GEEK! GEEK!), all in the hope of finding out quite why I bothered doing all of this in the first place. Circular logic? Trust me, you don’t know the half of it!

Sounds like a good reason to go all *SPOILER* crazy and Panel Madness one of the final images from the series in the hope of finding out why I can’t get this song out of my head, eh?

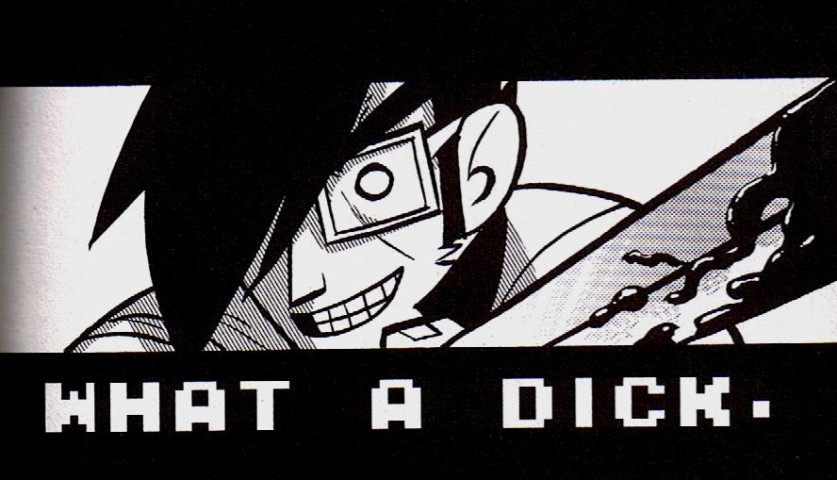

Well, this guy thinks he’s already been there and done that and built an inescapable black hole out of the image that we’ll be spending our time with…

But don’t worry about him – he’s just some guy from the story!

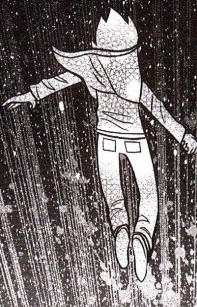

Here we go then, let’s think about this picture from Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour, let’s go through the same routines “once more with feeling”:

FIVE WAYS TO READ THIS PANEL…

(1) AS THE POINT WHERE READER IDENTIFICATION BOTH REACHES ITS APEX AND BECOMES IMPOSSIBLE

In the second post in this series, I had one of my customary digs at cartoonist/theorist Scott McCloud, but while there’s a lot to be sceptical about in the man’s work, it still has its uses. For what it’s worth, I think Dylan Horrocks’ essay on Understanding Comics is a lot more thoughtful and exciting than the comic itself, but that’s an argument for another day!

The first time I saw that panel from Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour, I started thinking about what McCloud says about about the universality of cartoon imagery in the first chapter of Understanding Comics:

The cartoon is a vacuum into which our identity and awareness are pulled…

…an empty shell that we inhabit which enables us to travel in another realm.

We don’t just observe the cartoon, we become it!

That might sound like an invitation to start talking about fun with fictionsuits, or it might just strike you as another one of McCloud’s unsupported assertions, but I think it’s oddly relevant to the Scott Pilgrim experience.

I mean honestly, which of these two are you more likely to identify with:

Maybe you wouldn’t want to associate yourself with either of them, and fair play to you! Certainly, there are plenty of people who actively hate George Michael Michael Cera, possibly because he’s found so much success as a bumbling everydork. Anyway, McCloud’s theory is that our own understanding of how our faces look is abstracted, because we only have a vague, internalised idea of what our faces are doing at any given moment. McCloud reckons that this makes us more likely to relate to cartoon characters because their crude simplifications reflect the map of our own features we hold in our heads.

I’m not entirely convinced by this, to be honest. I think that I have a wildly inaccurate idea of how my face looks at most moments, but rather than reducing everything down to its core elements, I tend to imagine an idealised version of what my face looks like at any given moment. Given the hoots of laughter that have greeted some of my previous attempts to look HOTT or dashing or interesting, I’m comfortable saying that I often have no idea what my face is actually doing, but maybe in a way that’s more likely to make me associate myself with Hollywood proxies than with stick figures.

What interests me about this image is that it takes facial identification right out of the equation at the story’s climax, at the exact moment that Our Hero leaps off into the unknown with Our Heroine:

And… it’s entirely possible that it might just be me, but I’m definitely able to put myself more directly into that panel than I was with pretty much any single image in the previous five volumes. Oh sure, the general outline of both the plot and the character of Scott Pilgrim fitted pretty well with my self-image during the years 2004-2010 — slobby guy is luckier with women than he deserves to be, gets too caught up in his own precious little life to pay proper attention to his friends, pursues the gorgeous girl with the constantly changing hair colours until she agrees to be with him then spends the next few years fighting to make it work — but these were pleasing resonances and little more. It’s not like these details were so specific that they might trick me into mistaking the story for a mirror, you know?

With the last couple of volumes, I’ve also been aware of the fact that Scott’s version of getting it together was even more shambolic than mine. Which, given the meagre achievements I’ve wracked up in the past decade, is really saying something!

Still, staring into that image, I have no problem placing myself in it right fucking now. There’s a different kind of abstraction to be parsed here, isn’t there? One that doesn’t quite map onto what McCloud was talking about, or indeed what I was talking about a few paragraphs ago. Instead of seeing our own face reflected back in a random collection of lines, what we have here is an abstract idea that we can recognise as such while still wanting to live it.

It’s not exactly unique in this regard, of course, and I think most people have trained themselves to be cynical about grand images like this, to the extent that it takes a lot of work to make them seem like anything but an advert in waiting. Thankfully, Bryan Lee O’Malley has spent several hundred pages providing reasons for the reader to care about this moment, and weirdly, I think this makes it easier for you (the reader!) to bring years of your own experience to the table. After all, those aren’t just stock figures, hanging suspended on the edge of finality, just waiting for you to invest yourself in the moment, to take the drop. It’s not a trap, it’s a story, okay? One that might be similar to your own life – but, you know, only to a certain extent! – so it’s safe for you to see yourself in the moment, to feel those made patterns flying up towards you, to let yourself fall through the story rather than into it…

…whatever the fuck that might mean.

(2) AS ONE LAST POP CULTURAL METAPHOR DESIGNED TO FREE THE READER FROM POP CULTURE METAPHORS

Another thing: how abstract is this image, really? Like a really awesome move from an action film, it’s repeating over and over in my head, taking on the meanings that I want it to have in the process. Let’s try to see it clearly one last time, before it gets blurred beyond all recognition:

For all that Scott and Ramona are disappearing into a dazzling mess of shapes and white light here, this is really just one last, triumphant video game reference. Or perhaps that’s too dismissive a way to frame it? After all, Scott Pilgrim has always been about two very different kinds of love, the love of pop culture and the love of unobtainable girls who can’t stop changing their hair colour.

(And where does that combination take us? Hmm… let me think on that!)

These two different types of fantasy have been intertwined throughout the duration of Scott Pilgrim’s run, so it’s no surprise that these fantasies reach fulfillment in each other at the end!

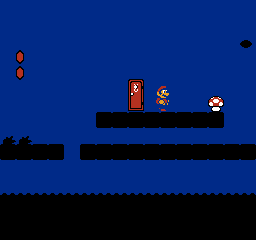

A few earnest souls tried calling this mix of everyday bullshit and metaphor-turned-metonym “Nintendo Realism” back in the day, but that’s a terribly clumsy way to annotate what’s going on in the book. I’m glad the description hasn’t stuck, but it’s not an entirely useless term – for one thing, its sheer gracelessness highlights how natural O’Malley managed to make even his most obvious flights of fancy seem. Which is really no small feat when you’re talking about shit like this:

What is “this” though? Well, the above image sees Scott and Ramona dropping into subspace, which, as Jog has already noted in his review of the Scott Pilgrim movie, carries with it a lot of very precise connotations:

Let’s put it this way: both of these things end with a happy couple plunging into subspace, ready for the unknown. But only one of them seems aware that when you enter subspace in Super Mario Brothers 2 — not much of a kick-ass fighting game, that — some established rules are reversed, and those shitty vegetables become gleaming coins, there dug right out from the earth. I know which one I prefer.

The question is, how much does this page gain when you’re aware of the implications that Jog describes above? You’d probably get the general feel of what’s going on just fine without bringing any arcane pop cultural knowledge to the picture — like I’ve already said, images like this are the stuff that advertising is made of. Still, the more information you bring to this image, the more you might be able to imagine what you’re falling into (through?).

Gold coins growing out of the muck of the Earth? We’ve been here before! Even taking this on board, there’s still ambiguity to this conclusion, still a sense that everything might not work out. It’s still given a little more specificity if you’re able to see something more than lines on the page here though, a sense that this pop culture reference might take both the readers and the characters beyond these references, or at least that it might necessitate new references, ones beyond the scope of what’s come before.

Now, since you’re reading a comics blog there’s a fair chance that you’re a bit too immersed in certain facets of pop culture, that you have a tendency to see everything from romantic politics to the real deal in terms that are a couple of steps removed from reality, that you’re someone at least a little bit like me, basically.

Or maybe you’ll resent this implication as much as you resented the idea of seeing yourself in either Scott Pilgrim or Michael Cera?

Meanwhile, over at A Trout In the Milk, Plok has been working on his own series of posts recently. There have been several intersections between what he’s writing about and what I’m writing about, but the second post in the series is the one I’m going to focus on right now. It’s about Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, and the following excerpt is crushingly relevant to the thoughts that I’ve been working through here:

And you know, one of the great things about this for me was the Canadianness of it…I deeply recognize the locales as wonderful analogues of the places I lived in, the places I went to. BACK THEN. Through the airport glass. But for my good friend over there, they actually are the places he does live, they are actually the places he doesgo…and there ain’t nothin’ analogic about it, and besides that it isn’t great. Because they are loving looks at those places, but they are not his loving looks. Though not a single soul will ever come riding to the rescue of an averagely white guy who feels colonized, still that’s exactly how he feels, and he’s not wrong. We’re all colonized, some time or another. But some of us, strangely enough, are supposed to like it.

Reading Scott Pilgrim, it never hit so close to home that I started to resent it, but I can certainly understand how it would piss you off if you did feel like you were having your own life sold back to you.

But is there a third road here? One that runs between being absorbed in the references and being disgusted by them?

Is there anywhere you can go from here?

(3) AS AN ADMISSION THAT WHILE THE AUTHOR MIGHT BE SICK OF THESE CHARACTERS, HE CAN’T IMAGINE THEM ANY OTHER WAY

If you find yourself asking that question while looking at this panel, you might not be the only one. From the sound of it, Bryan Lee O’Malley’s been asking himself the same thing recently:

And yeah, you know, I was so stoked on the Invisibles around the time I first started thinking about pilgrim. I came to Morrison late, but of course I branched out and read the PKD and the science and the Gnostic texts and everything. And now I see kids doing the same with pilgrim but it only leads to dead ends like Nintendo games.

I worry that all I’m good for is examining the contents of my own brain, like I can’t make new neural connections or something.

OH WELL.

(From the conversation between Matt Fraction and Bryan Lee O’Malley in the back of the Casanova: Gula #1 reprint)

Quite a loaded little quote, that. The first half seems to indicate that O’Malley conceived Scott Pilgrim as being a jumping-off point for ambitious young fictionauts, while the second half speaks to the realisation that this particular escape route leads nowhere but the inside of your own skull again:

By this point in the post, you’re probably getting a little bit too familiar with that feeling, but I think it’s fair to say that you could see O’Malley struggling with this anxiety in the last couple of Scott Pilgrim comics too. Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour runs through the tropes that have been established in the previous five books in order to escape them, but only after that numb opening stretch in which Scott retreats from his story, and therefore his life. It’s an odd sequence, in which Scott is reduced to obsessively playing computer games instead of living them. Of course, the story builds back up to a suitably grandiose finale — the last two thirds of the book are taken up by the most detail-heavy fight scene that O’Malley has ever conceived — but even when it’s at its most dramatic, you still get the sense that even Scott Pilgrim is fed up being in Scott Pilgrim:

This feeling has permeated the last couple of books, but where volume #4 saw Scott taking baby steps into responsible adulthood and volume #5 suggested that there were more interesting stories going on in the background, this sixth volume attempts an odd hyrid of the two. No matter what tone Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour adopts, it never stops beating the main character over the head with his own ignorance. Did you wonder what the deal was with Stephen Stills? Well, then apparently you were paying more attention than Scott, because it turns out Stephen came out to the rest of his friends in volume 5 without Scott being either present or being interested enough to find out.

Hence, to win the final battle in this book, Scott needs to discover The Power of Understanding! Love is not enough – he’s got to be able to see past himself, if only for a few seconds. More than that, he’s got to learn to recognise himself in his enemy. At the same time, it also seems like O’Malley can’t imagine these characters any other way – which brings us back to the ending, and to this panel again:

Looking at it as an image, as a series of shapes on the page… well, this is a depiction of the moment where the known hits the unkown, isn’t it? I’ve already outlined the roles that reader identification and pop culture knowledge play here, but the same themes play out on a purely visual level too. You’ve got Scott and Ramona, hanging there, frozen at the point where darkness and pure expressive potential meet – the previous page saw them moving from inky oblivion into a mess of texture, and the next few pages see them absorbed in the blank canvas of the empty page, but for this moment they exist somewhere between an overly defined moment and a totally undefined one.

Separate Scott and Ramona and you can see the fact that the patterns they’re falling into are part of them too now. They’ve both absorbed the rich textures of the stories yet to come, but what happens in those stories is very much left to our imagination, to the blankness that follows.

It’s not hard to feel a little cheated by this – what’s the point in making such a fuss out of Scott’s lack of empathy when we’re not going to actually see how well it serves him in practice? – but Scott Pilgrim’s actually more honest than most stories on this level. At least this climactic image is intentionally ambiguous, you know?

This is the not terribly well-kept secret behind all happy endings, especially romantic ones: for most people, the story doesn’t end when the credits roll. Love isn’t a destination, but an ongoing process, a thing unto itself, he says, paraphrasing an obscure Alan Moore comic that no one really bothers with. The big dramatic moments are important, sure, but so’s the stuff you have to do every day, the small pleasures and irritations. The stuff that doesn’t always make for good action comics, basically.

What does life after this moment look like for Scott and Ramona? I don’t know, and perhaps Bryan Lee O’Malley doesn’t either. Maybe it’s better that way though. Maybe, just maybe, it’s right to let them have the freedom to potentially be anything…

(4) AS SOMETHING THAT REMINDS YOU OF A SCENE FROM ANOTHER STORY

Of course, that only works if you’ve got both imagination and the capacity to let things go. I like to think that I do, but that’s just a story I tell myself so I can sleep at night.

So: back on the pop culture roundabout then! Two characters leaping into the unknown, regardless of the obvious differences and difficulties between them… yeah, I’ve seen this before! I’m sure you have too, but it turns out that I’m actually a bit of a a sucker for this finale, probably because some of my favourite stories end this way. Seaguy: Slaves of Mickey Eye comes to mind, as does Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – which, hey, pop culture references and girls who keep changing their hair colour! I knew we’d get there in the end.

All joking aside, both Seaguy and Eternal Sunshing make for interesting comparisons here. Seaguy (the comic, rather than the character!) is all about surface, so it makes sense that all Seaguy and SheBeard have at the end of volume 2 is the idea of each other. He’s the one weirdo who cared enough to stand up for something, to stand up for her; she’s the proudly aloof oddball who refused to take the world on any terms other than her own – together, they fight crime!

Or at least they might, and that’s enough for this moment, for this one image. Especially in New Venice where, as we’ve already noted, surface defines! It’s probably worth noting out how static this image is, compared to the one from Finest Hour. You know that those two have got to move on eventually, but at least the ground seems to be solid underneath their feet. Even inside this moment though, sinister hints abound, hints that those crossed swords represent something other than two personalities at war. After all, that’s hardly a picturesque backdrop they’re making out in front of! Here’s Jog, The World’s Greatest Comic Book Reader, uncrossing the references so you don’t have to:

…there’s another part of this issue I love to pieces, the very last page, and while it’s a decent enough grace note on its own, you really don’t get the full impact unless: (A) you’ve read New X-Men; (B) you’re aware of the proximity of the original Seaguy’s release to a troubled genre situation at Marvel; and (C) you recognize how the in-story idealism of the older work applies to the commentary-on-the-refutation-of-that-idealism of Seaguy by again becoming in-story idealism.

And isn’t that a neat, half-short and twice-strong version of my whole argument here? Damn but that Jog kid is good. If only more people read his stuff! All of this gets me thinking – how much do Scott and Ramona only work on the surface? Is she Scott’s Manic Pixie Dream Girl? Is he Ramona’s Knives Chau? Is the ending about them acknowledging that there’s more to each of them than that and trying to live with that?

Which… hey, wouldn’t it be great if there a was a whole movie about how hard it is to decide to carry on with a romance, despite all of these problems? Oh, that’s right – there is! Here’s something I wrote about Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind a while back:

The final section of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is nothing short of spectacular. It’s a headlong rush of uncomfortable awareness for the two main characters, and, in an odd way, what it reminds me of more than anything else is Donnie Darko…

It seems to me that Donnie Darko captured so well was a feeling of confusion that gradually transformed into some sort of weird mixture of knowledge and acceptance in the face of overwhelmingly deterministic forces. Something similar happens at the end of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, with Joel and Clementine facing up to the reality of how their relationship is likely to work out, and deciding to go with it anyway…

Lets just put it this way; the ability every one of us has to accept the distance between what we feel we need and what we know that we will end up getting from any given person is both sad and wonderful, and I can think of no more eloquent and poetic expression of this than the final looping segment of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Well, the ending of Eternal Sunshine might still have something on the end of Scott Pilgrim, but even without that recursive loop, Scott Pilgrim’s finale manages to hit a lot of the same notes. What you see in this panel are a pair of looking glass hearts frozen forever. You know that feeling that you want to take a chance on someone, knowing full well that you’re both probably seeing only what you want to see in each other? This panel is that feeling, shrunk down and blocked out in black and white.

Not bad for an image that’s almost fading out of view now, eh?

(5) AS ONE POSSIBLE ENDING IN A SERIES OF POSSIBLE ENDINGS

I’ve already recycled that bit about Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind once before, but I figure it’s not worth writing something new on the same theme unless I’m sure that I’m also writing something that says the same thing better.

Speaking of which, how about that movie adaptation? It’s a deeply odd viewing experience for the experienced Scott Pilgrim reader, with familiar images, scenarios and lines of dialogue being replicated with extreme fidelity, but often in the “wrong” place. It’s like looking through an old and familiar photo album only to see your Uncle Bob with his hand up the fluffy ostrich puppet when you know it should be your Aunt Barbara. Which is to say: the ending of Scott Pilgrim vs. The World stops just short of this panel. It literally takes Scott and Ramona right up the door into, but the camera pans up instead to an old school Continue? countdown that’s straight out of Mortal Kombat.

This is a good ending, almost good enough, but while it hits all the same notes as the end of the comic, and does so in a fitting style, I can’t help but feel the absence of that final plunge. The movie’s ending is just that little bit more coy becuase of this change in emphasis, and… I’m aware that Bryan Lee O’Malley probably hadn’t even drawn this image by the time that scene was shot, but I miss it all the same.

As Jog has already noted in his review of the film, there are many ways in which the comic is more affecting and well balanced than the movie. He also suggests that it might be, well, a little girlier than the film. You know, in a good way:

…while I wouldn’t call O’Malley’s comics gender-bendable in character-based terms, they are unusual in drawing so much influence from girls’ or women’s manga; people seem to ‘remember’ the fights in Scott Pilgrim, but until the final volume they’d typically only take up a handful of pages, sometimes ending in an evil ex making a terrible mistake steeped in their own hubris, but usually at least slathered in character dynamics. People getting to know each other, teasing out their secrets: folks joining the party. Video games don’t have to be all fights, you see.

All good point, all made with an efficiency that could make Edgar Wright turn green. Still, I’m not here to set the movie and the comic against each other in a death match for the audience’s affections. Indeed, the more often I see Scott Pilgrim: The Movie, the less capable I am of critiquing it clearly. Watching it is almost like watching Edgar Wright power gaming his way through the story of the comic, a simile that syncs up nicely with the conclusion to the film, in which Scott uses his extra life to play the last level again with no fuss and plenty of fury. SPvTW is also the most energetic and exciting romantic comedy I’ve seen since Punch-Drunk Love, with that film’s sudden explosions of sound and colour replaced with Wright’s wry take on various genre tropes. And for all that the film is mainly about the fights (and all the percussive noises and sparkly explosions they entail!) it still has moments of witty sensitivity.

There’s this scene, which in which one of McCloud’s cartoony facemasks becomes not a blank canvas, but a jarringly expressive one when Knives Chau geeks out. Come to think of it, many of the best sequences in the movie involve Knives – my favourite one comes near the end, when Scott bumps into Knives in the middle of a crowd full of people who have just watched his band bring the house down. He brushes her off, because the demands of the plot are pushing him onwards, but for the few seconds she’s onscreen the soundtrack switches out, the lighting changes, and we’re in Knives’ story, in which this is a pivotal moment rather than a temporary distraction.

Of course, this moment relies on Broken Social Scene’s ‘Anthems for a Seventeen-Year-Old-Girl’ for a lot of its impact, and the question of how much the fragment of the song we hear in the film is enough to carry the scene without prior knowledge of its greatness takes us right back to (2). Still, if you know the song, if you love the song, this moment kills. If Scott could hear it… well, he’d be a monster not to spend a little bit more time with her, to make sure he was letting her down a little bit more gently before setting himself up for a fall.

Knives isn’t in that image, and she isn’t in the scene that replaces it in the movie, but there is an alternative ending to the movie in which she ends up with Scott and Ramona takes the leap on her own. This is the ending that Edgar Wright was originally building up to, and you can watch it here.

Here’s what I had to say about this alternative ending in the comments to Plok’s Scott Pilgrim post:

Ah, see, now I think the romantic reconciliation with Knives makes sense, IN AN EDGAR WRIGHT MOVIE, even though it doesn’t make sense for Scott Pilgrim (the movie/the character). Wright’s such a tidy worker, and the original ending has the sort of circular structure that he favours – think of the way that Hot Fuzz has to come back to the Aaron A. Aaronson joke in its finale, just so you know that everything is in its right place.

In the original ending Scott’s smile fades during the final moments as he looks into Knives’ eyes, which… Wright flags this up in the commentary, a little Graduate riff, he calls it. So… that cut of the movies collapses back into all that’s easy and pleasurable and “childish”, but then says it might not be enough. The theatrical version forgoes all that for another sort of childishness, but… well, Scott Pilgrim (the movie/the character) is all about the pursuit of that unattainable girl, and I’m glad they went for the messy, open, let’s try again finale instead. Looking glass hearts forever, that.

I still can’t shake the feeling that, in the movie at least, Scott is still Ramona’s Knives, but… there’s maybe something more to be said for trying to keep all of these endings, with their differing inflections, in your head while thinking about that image. After all, both the comics and the movie are hyperlinked romances, with every pop culture reference a doorway into something else – why should the ending be any different?

If you’re still not convinced, try thinking of the endings as different possibilities that await you at the end of a game – that might help, because hey, it’s almost like real life, except you can play through it again with different resutls! Here’s the thing though: none of the possible endings to Scott Pilgrim’s story are entirely positive, but none of them are entirely hopeless either, and that’s fine. In fact, that’s absolutely perfect here.

It’s easy to fall in love with someone, but staying in love with them? Shit, that’s even harder than trying to communicate your experiences meaningfully in this heavily mediated world. What all of these endings acknowledge is that while it might not work out for everyone, it’s probably still worth giving it a try, contra Josie Long. Each ending also comes loaded with the knowledge that people don’t always know what they want, but it’s very clear that all of the possible participants wants something more than what they’ve got here. Whatever the result, it’s better to accept that you might get hurt than to mimic the villain of the series/that dick from the start of this essay, Gideon Graves, whose grand plan involves freezing the girls who’ve left him rather than letting them be who they are.

As with experiments in pop culture metaphors, attempts to make a troubled relationship work are easily corrupted by displaced solipsism. You can try to see someone clearly and see nothing but your own thoughts and hopes and fears reflected back at you, but only a real bedwetter would flinch away from trying to see something more than themselves there.

This is the pivotal drama of the Scott Pilgrim comic book, the attempt to break free of “the glow”, a geeky technology that Gideon (Ramona’s most evil ex!) has developed to keep people trapped in their own thoughts. It’s almost trite, but again, that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying for.

So: what do I see in this image…?

I see something impossible disappearing in front of my eyes.

I see something stupid and beautiful and ridiculously subjective, and I know that I don’t want to let go of it, not now and not ever…

Continue?

CONTINUE?

CONTINUE?

CONTINUE?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.