Dis-orientation

March 28th, 2020

Esther McManus – Windows (See You at the Potluck, 2018)

This one comes from what my partner calls the “They Saw You Coming” side of the comic/zine world. Every time I visit a comics festival or zine fair I come back home with at least 2-3 books full of pictures of buildings, or parts of buildings, or spaces where buildings used to be. I rarely regret it.

Esther McManus’ Windows is an excellent example of the form, a series of portals that have been removed from any supporting context in a way that serves as startling prompt to the imagination:

The work demanded by this zine doesn’t just come in the form of having to reconstruct the urban environment – that’s the most immediately striking element, of course, a natural by-product of the composition of the piece, but it’s the start of a process rather than its final conclusion.

In its gradual blurring of the distinction between windows and the shapes that frame them, its removal of the human from the urban environment, and its finding of new ways to recombine familiar shapes, Windows is ultimately more Ballardian in its effects than it may initially appear.

Moving beyond brutalist cliches, this is a work that re-imagines the city as something that is no longer for us – a space that exists on the other side of the portal, where there is nothing to be reflected except windows looking on windows looking on windows all the way down.

It is March 2020. I suspect that this scene is more familiar to many of us now than it would have been at any previous point in my lifetime.

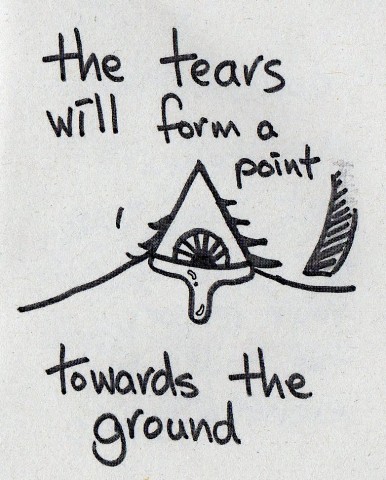

Sarah – How to Cry At Work (self published, picked up a Ghost Comics Festival 2019)

Of the handful of amusing and attractively illustrated mini-comics Sarah had on sale at Ghost last year, this is the one that most demands wider distribution.

At the time of writing, many of our workplaces have evaporated with the rain. Of those that remain, the working conditions for some are now implicitly more dangerous, while others have rendered themselves safe by colonising our homes. Whether you consider it on the broader social level or on an individual scale, work was obviously unstable before any of us had ever heard of Covid-19; control of our labour – and by extension our working lives – is rarely in our hands. Those with more control, meanwhile, often seem frighteningly keen on getting rid of whatever insulation exists between their realm and our own.

In this context it stands to reason that wherever there is work there will be tears. Enter this small pamphlet, which does exactly what it proposes to do by providing good advice on how to cry in a working environment, and which did not in any way deserve to have all of this windy preamble inflicted upon it.

Trust me when I say that that this advice works equally well at home.

Pete Krause, Jose Marian Jr and Cindy Goff – Metropolis S.C.U. #2 (DC, 1994, picked up in a charity shop on a whim)

It would probably be glib to look at the disoriented storytelling of this comic’s opening scene -which depicts a training fight in a fake urban landscape with such cackhandedness that all sense of geography is lost – and see a political justification.

It would be glib, even, to read such a scene as storytelling. It is pure folly to imagine that these pages are designed to emphasise the disorientation of the rookie cops depicted, who – if their un-tethered surroundings are anything to go by – must be spinning on the spot in wonder to find themselves in such a scene. Whether examined in the moment or taken as a whole, this isn’t a comic that successfully nails mood.

On one page, we establish that we are dealing with procedural detail in a fictional universe imagined for children. On the next, we’re treated to a jail break straight out of a cartoon from a different era:

For the most part these clashing modes exist on the one page, providing none of the satisfactions either extreme may have to offer and none of the joys of a successful hybrid form. This is not a new story in comics, and the fact that this isn’t a new comic doesn’t even offer much by way of a worthwhile perspective – it just makes it feel like an uninteresting footnote in an unloved chapter of a deeply uneven book.

When the story climaxes with a cop shooting someone dead in another poorly composed action sequence, followed by speeches from a shook Louis Lane about how she just wants to make sure that people understand how hard it is to be a police in Metropolis, home of Superman… well, these storytelling deficiencies start to feel more sinister, like piece of rote propaganda that – through accident or design – can only work to justify an itchy trigger finger.

It’s a glib point to make here, for sure, but the treatment of these same topics on the comic page is even less attentive and all the more reprehensible for it.

Douglas Noble – Here Come the Beautiful People (Strip for Me, 2017)

Speaking of uncertainty, of a sense of unmooring, we find ourselves back in the company of Mr Douglas Noble, a known confidence man and “psychic” fraud of low character.

Mr Noble may often be found relying on his capacity for mystery and showmanship to part easily influenced comics readers from their money. At the moment, he is giving this particular comic away for free, in what appears to be a fit of unmitigated generosity but surely masks a purpose too sinister for easy contemplation.

In Here Come the Beautiful People, a series of short stories set in the Riviera, such mystification has an overtly sinister aim on the spiritual plain as well as the material one: to put it bluntly, this involves the destruction of a humble and noble character.

The first three stories here concerns couple of mysteries that will find resolution of sorts in the fourth. Missing dogs are given more weight than dead women in these stories, which may tell you something about the low morality of the imagination at work here, or which may be intended as a reflection on the priorities of the world depicted – I am not a Dickens character, so I see no need to be charitable in my readings of the many inky phantoms of the world’s library.

As is often the case in Mr Noble’s experiments, visual information is conveyed to the reader in an elliptical, fragmented way, but careful observers will note that Mr Noble allows one name to be gently slandered in the first three stories. The fourth story is a piece of outright character assassination, in which the lowly and the maligned are re-imagined in a satanic light. Having laid the suggestion of omnipresence in the previous stories, and suggested a certain logical culpability, Mr Noble escalates his victims to the status of Morrisonian author-gods, linking all the world’s miseries to their actions.

We must be careful not to be manipulated, readers. The wicked Mr Noble has designs on our debit cards and our souls. He has the skills and the temperament for success. He must be resisted at every turn. He is not the only one.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.