All Star Superman: Man Made/The Gold In Us

May 20th, 2015

A few thoughts about working for Marvel/DC, as stolen from a Canadian friend who was trying to add a bit of clarity to my rant about Chip Zdarsky’s inability to say the name of Howard the Duck‘s “original creator”:

(1) In corporate comic, everyone is a scab because there is no union.

(2) In corporate comics, no one can be a scab because there is no union.

(3) Join the union.

What to make, then, of Grant Morrison’s dedication to superheroes, his attempts to imbue them with some sort of positivist power of their own, to try and find transcendent meaning in a series of commercially dictated genre tropes and characters that were sacrificed to them? When presented straight, in Supergods, this stuff feels as silly and desperate as it is, like an attempt to put a fresh golden frame around a thrice-stolen turd in the hope of selling it on eBay again. But in All Star Superman? Not so much. The sales pitch here is a lot more successful.

I was being dumb and scatological there, for sure, but the emphasis on framing is appropriate. This is Grant Morrison’s most carefully crafted book, the one he says that he “wrote for the ages”:

It’s the one that comic fans really like. They like that, you know, that architecture… It’s literary, it’s not like a live performance. Like, you read The Invisibles a hundred times and it’s different a hundred times. If you read All Star Superman a hundred times you just understand it more.

In other words, as I think he’s said elsewhere, it’s his Alan Moore comic: twelve issues, immaculately constructed as a hall of mirrors instead of Watchmen’s inkblot test, with Superman wrestling with other versions himself issue after issue as he works hard to deal with the aftermath of his own murder.

In issue #3, Sampson introduces the idea of Superman completing “12 super challenges” before his death, and while trying to work out what these challenges are provides the reader with a way into this series, this comment is more telling for its focus on the level of effort involved both within the story and in its creation. This is the book, after all, that starts with a three-panel origin story, then launches straight into a double page spread in which Superman flies into the sun to save the day. In other words, this version of Superman is no sooner born into this world than he is put to work to save it.

The remainder of the story follows suit, with our hero working at least two jobs as Superman and Clark Kent, maybe even more if you count looking after the museum/zoo that is The Fortress of Solitude and working as a scientist – these latter two duties fill his time when he takes Lois Lane back to his gaff for a post-death sentence date.

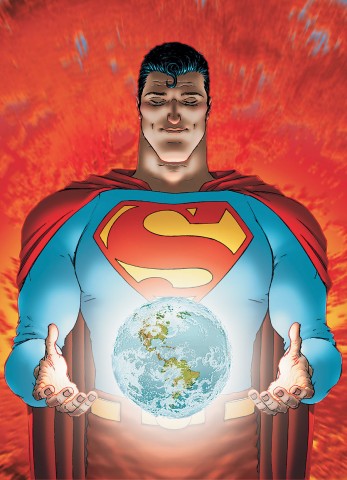

This is where Frank Quitely and Jaimie Grant come in, because for all that this version of Superman spends the whole story in motion, the effort rarely shows. Here’s an exemplary All Star Superman panel:

In Frank Quitely’s previous work with Morrison and Grant on We3, he allowed the details of the environment to interrupt the procession of panels, giving every page turn a sense of latent chaos and danger. In All Star Superman, by contrast, Quitely’s composition is calm and steady throughout, with his unfussy, page-long panels creating a feeling of steadiness and solidity that is given depth by Grant’s immaculate lighting. Quitely’s Superman rarely looks like he’s straining himself – as in the above image, you get a sense of his force from the effect he has on the world around him more than from the posture of the figure himself.

That’s why it’s the scientists on the furthest edges of the frame who show the most reaction to Superman’s herculean efforts: those closest to him can see only the calm of the man himself, so they share in his assured sense that he is at one with his labour.

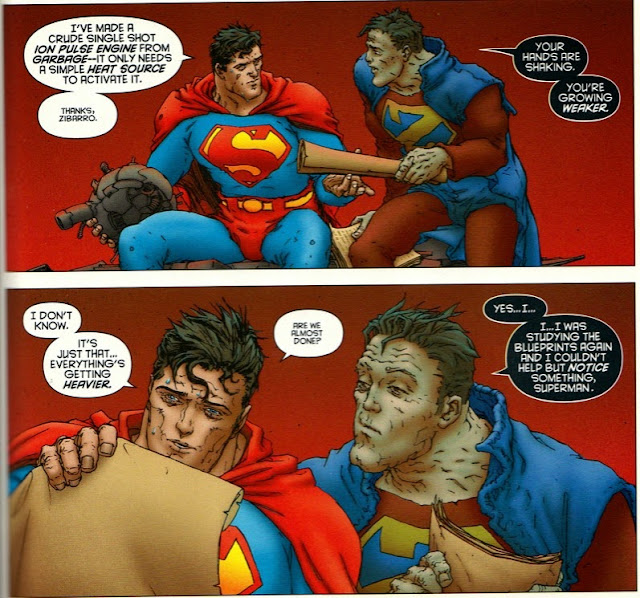

This is what makes the trip to the “underverse” in issue #8 so disturbing. For the space of a whole issue, we are presented with a version of Superman whose efforts seem futile, whose companions reflect his own blatant absurdity, and whose physical form seems to be coming apart in front of our eyes. The whole series has something of this effect to it – it’s the story of what happens to your story when your ability to keep on telling it comes into question, after all – but the sense of calm usually keeps that tension in the subtext. In the Underverse, meanwhile, Quitely’s line takes on an itchy, ragged quality; there seem to be more lines in Superman’s face here than there were before, and none of them are so clean and certain as we might have come to expect. In episode 8, US DO OPPOSITE, the reality of death is suddenly inescapable:

Superman may escape from this reality, but he is unable to bring Zibarro with him; again, there are limits on what he can achieve in this plane of existence, just as there are in ours.

On both sides of that little trip to hell, Morrison, Quitely and Grant work to imbue Siegel and Shuster’s creation with a sense of meaning and purpose, portraying him as a man who is able to work for the benefit of others even while facing the reality of his own failures and limitations. Death happens to all of us, and work to most, but if few of us use the knowledge of the former to motivate us to do so much good for others then we may at least console ourselves with the fact that we’re better able to manage our romantic lives than Superman appears to be.

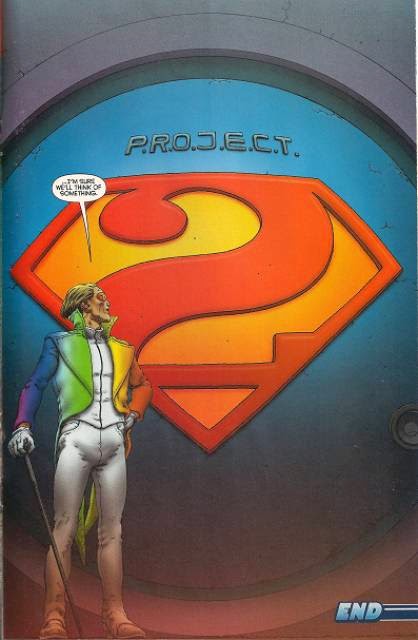

Unable to return Superman to his creators, the workers hired to toil on this particular version of Superman imagine an endless, looping fantasy wherein he is both created by and the creator of those who gave him life:

If Morrison’s rhetoric about Superman being “our greatest ever idea as a species” can be read as an act of complicit erasure of the character’s creators, this sequence from All Star Superman #10 is a more successful synthesis of hyperbole and reality. Here, the character’s origins in this world are recognised as part of the attempt to make them more than mere product.

“SUPERMAN YAY!” OR “SUPERMAN BOO!” – ???

But is this not merely a more effective form of marketing, one that provides the sharp-eyed reader with vision of work made good that is so beautiful as to convince them of what they know to be untrue? I’m voting “Superman boo!”, then, because I don’t want to feel like I’ve been fooled and because most of us are more like Siegel and Shuster than we are like the people who currently own their creation.

At the same time, if this one comic isn’t quite beautiful enough to bring about a world in which our products are only so many mirrors in which we see our essential nature reflected and reflecting, it nevertheless succeeds in suggesting the possibility of such a world.

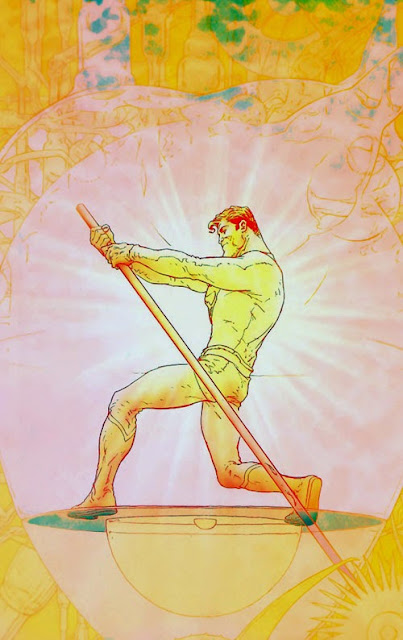

Another exemplary panel then, in which our hero takes up his place as an eternal labourer at the heart of the sun:

It’s an ambiguous image, in which Quitely’s Superman is frozen in the heigh of his power and confidence, servicing human need both inside the story and outside of it. At this same time, this is also a vision of life unnaturally suspended, of a #brand that just won’t die. Faced with this, how can I do anything else but vote “Superman Yay!” as well? What can I say, I’ve got a Superman t-shirt and sometimes I wear it to both ask myself why we do so little with the capabilities we have, and to remind myself – as if I truly need reminding – of the ignoble nature or so much of our work.

Maybe we’ll finally get it right this time, or maybe it’ll just be another day in the office, but either way I’ll see you all later…IN THE NEXT EPISODE!

***

THE ABOVE IS AN EXCERPT FROM MY CONTRIBUTION TO THE LONDON GRAPHIC NOVEL NETWORK’S DISCUSSION OF ALL STAR SUPERMAN.

I’ll BE POSTING ANOTHER SELECTION ON THE INTERACTION BETWEEN FAITH AND SCIENCE IN THE COMIC NEXT WEEK…

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.