PaxMan: An Experiment in Assisted Re-Viewing

December 10th, 2014

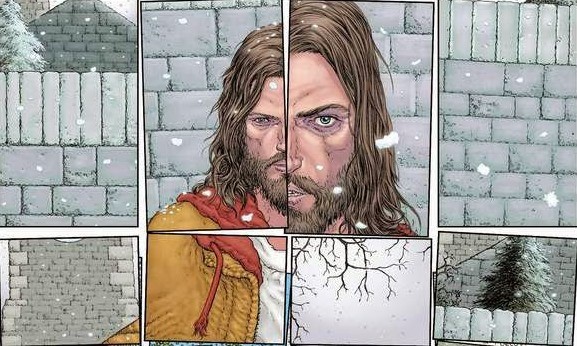

Frank Quitely, Grant Morrison and Nathan Fairbairn – Multiversity: Pax Americana #1

It’s here that our story begins: in pieces. Many, many authors have shot at this target and missed, preferring not to recognize that in truth this is what we really know, and what we really believe, about the forces that create and shape our lives — preferring not to see that what science and philosophy describe is the branch from which our lives’ dramas depend, and not just convenient intellectual set-dressing for them.

We should remember that murder mysteries are always just local expressions, of a grander philosophical struggle — someone is killing capes, and who’s next? Well, after the scientists the answer is, we are: as the stunning profusion of interlinked symbols that fills Pax Americana’s pages ceaselessly intimates to us the unavoidability of that final, bitter realization of entropy. War, and death, and chaos…

…Or, what is perhaps worse: not chaos, at all, but order.

An implacable order, that we can’t resist. A pattern we’re trapped in, that we can’t see.

Nihilism is the watchword. Or is it? At the very least, I think we can say that any ideas of order that Pax Americana presents us with are quite explicitly man-made. All the Colossal Men, and Shrinking Women, and the legions of mutated monsters, and the superheroes…all so blighted by catastrophe and accident, but still striving to reassemble themselves into an ethical shape, framed in contrast against an impersonal universe. Not that we haven’t seen all this many times before, in the library of human storytelling; your Gilgamesh, your Cuchullain, your Herakles…but we can certainly that the antique pattern of human fables and myth acquires a new accent, forty years after Einstein. A new relevance. Suddenly, all at once, we are not just homo sapiens but homo sapiens atomicus — one step closer to the eschaton.

And we know it.

But in Pax American, possibly for the first time, we can also see it: because there are no images in the comic at all that are not weighted to exert this pressure on our reading. Can you look the world in the eye?

This isn’t just a work that was shaped by post-9/11 paranoia, cultural exhaustion, quantum awareness or a fear of ending up on the losing side of “the clash of civilizations” – it’s a work that craves a punchline, wants to knock us all dead, but which knows that nothing is ever fully or simply erased. Rest in Peace (RIP) does not mean “Sleep well” but “Do not return to disturb us”. We find it convenient to regard the people of the past as mere flotsam in the river of historical trends, passing ideas from hand to hand without ever making them…but the truth is that they do make them, and we just don’t like to think about it.

The odd “Great Man” standing like a mighty boulder in the current of events we can tolerate, but to assign a full intellectual agency to all the dwellers in the past would be to make the past too complex for our comfort: after all, if we make every molecule of the stream a Great Man, mustn’t we give up the idea of “current” entirely, abandon all generalizations and all statistics, and therefore relinquish every hope of meaning? And then where would we be. Only in chaos. So it’s much better for us to construct a story of history that we can comfortably place our own era at the end of, as a sort of product.

Pax Americana betrays an intense excitement and anxiety over the return of the dead, the return of comic book history. There is nothing here we haven’t seen before, nothing we don’t know as well as we know our own faces, because this is the one superhero origin-story we’ve all experienced. Maybe, the only one there really is: in an instant, the random distribution of objects and events sort themselves into the shape of a lock, that we fit into as a key, and turn…and suddenly a dead world is revealed as living, reactive, communicative…full of oppressive vibrations, to which we simple humans react as so many lonely tuning forks.

Yes, that’s the feeling, all right. The only unusual thing about it in this case, is that we get to see the deja vu from the other side…not that the present moment has happened before, but that it has been remembered before…

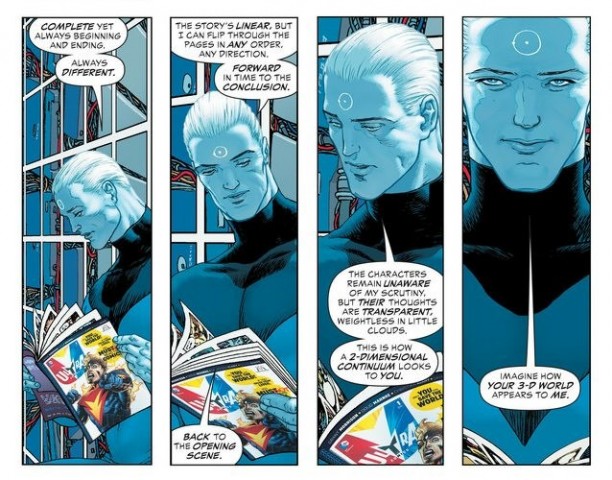

The structure of deferred action, as it is known in psychoanalysis, powerfully informs the reader’s understanding of this comic. The superhero stories read as a child or adolescent must be entirely reevaluated in light of such later knowledge as the revisionary superhero narrative provides; panels read on the first go through must similarly be reevaluated in light of subsequent, non-traditional movements through these pages; innocence reframing experience; each new reading turning those preceding it into imperfect synecdoches.

The flaws are there too, if you want them: the plot is full of holes; the symbolism can be over the top; the structure is suffocating; the geopolitics are crude; one misprision will follow another, each as arbitrary an orginisation as the one that came before. You get to a point where you discover that all the promises you thought were being made are never going to be delivered on. Not so much broken, as deferred. Satisfaction will never come. Nothing ever ends, but eventually all the politics comes tumbling out, the stuff that cripple superheroes – but without it, as an adult all you have is nostalgia.

What makes the book stand out in its immediate context is its aesthetic coherence: this is an authentic early twenty first century aesthetic, the product of two unique sensibilities at a particular moment in time, repeating.

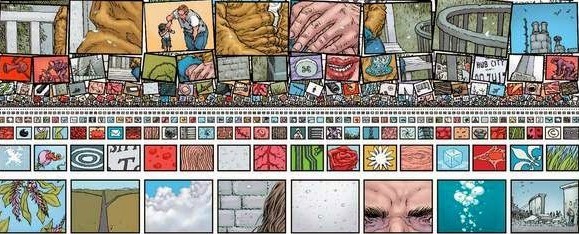

There are an enormous number of self-informing visual motifs here, planted in a very rich seedbed of allusion and yet from the recurring asymmetry of the blood stains (First Cause!) to the endless parade of reflections in every word, image, and panel. The visual/verbal punning serves to further intertwine past and present, and to confuse plots and narratives anticipated by the characters with the “reality” of what happens on the pages of the book – if we just look again we’ll see that in another sense it’s all accident. Of all the coincidences, synchronicities, and indicators of infinite connection Pax Americana shows us, there is not a single one that if seen from another angle or in another slice of time, or even simply in another order, would not miss its synchronistic connection…

And yet they would all still be there, strewn across the pages of the narrative like Rorschach’s sugar cubes, and that’s the point of this miracle; perhaps we wouldn’t be so fortunate as to notice them. But they would be there, as real coincidences: despite the story’s fantastic elements, there is nothing we are not intensely familiar with in the way they line up to offer possible meanings, because we’re well aware that’s what the elements of our own lives are wont to do.

Pax Americana features at least two (unsuccessful?) replacement gods, one more clearly willing to intervene than the other. But what is it they were supposed to do, in Harley’s plan? Were they supposed to prevent or limit human suffering, with the necessarily imperfect knowledge and understanding that even wildly intelligent pattern spotters or transtemporal beings are heir to? This parallels a fairly basic Christian response to the problem of evil: to force us to love is to remove our ability to love; to remove our capacity for evil is to make us robots, not humans, and ultimately to destroy us for our own good. In the age of quantum mechanics such a view is hopelessly antique: to Nathaniel Adam as to us, it isn’t that you can divine what’s on the other pages without having to turn them, but it’s that everything is on every page, all the time, continuously…and you can’t not intervene…

Because to see is to intervene.

We do not live in an abstract world. For us, meaning is a matter of concrete objects, people and events and attributes, details and facts and the endless attempt to know what things are in themselves…because somewhere beyond the approximations of our theories (all of which we will have to trade in when they become obsolete, only to get new theories that will become obsolete in their turn), beyond all our ideas about the world, is a real truth we would like to be able to reach out and touch, grasp, hold…

…But what about Captain Adam, who has had all of that taken away from him. “The light…the light is taking me to pieces.” And what residue can possibly be left? Like anyone else — like any of us! – Adam’s identity lay in all that was intrinsic to him as an individual, real, and concrete human person: he had a father; he had friends; he had a future and a meaning all his own. Well, just as we all do, until death peels them away, and we stop being anything — until we vanish from the world, and stop being real.

It’s here that our story begins: in pieces.

Primary textual source: William Ritchie, ‘At Play Amidst The Strangeness And Charm: Watchmen and the Philosophy of Science’ (from Sequart‘s Minutes to Midnight: Twelve Essays on Watchmen). Secondary textual sources: Geoff Klock, How to Read Superhero Comics and Why; Dave Golding, ‘Superheroes’; John Pistelli, Good Reads review of Watchmen; David Fiore, ‘Alan Moore & David Gibbons’ Watchmen’; Eve Tushnet, ‘OH, HOW THE GHOST OF YOU CLINGS! Notes on Watchmen’.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.