Doctor Who: Fifty Stories For Fifty Years — 1992

June 23rd, 2013

One of the things that people who want to defend the Doctor Who produced in the sixteen years the show was off the air often say is that it was hugely influential on the programme once it returned to TV.

Sometimes this is clearly not the case — very few people would claim with a straight face that something like War Of The Daleks (a story that only exists to retcon away every post-1975 Dalek story, because the author didn’t like that they contradicted a missing story from 1967) or Sometime Never (in which it is revealed that the Doctor isn’t a Time Lord at all, but a crystalline entity from beyondthedawnatime who had been evil until the eighth Doctor gave him some of his life energy, which made him look like an old man and think of himself as the Doctor) has had any influence whatsoever on any future writers, except maybe to make them think “we’ll definitely not do that then”.

But on the other hand, there definitely has been an influence. When the programme returned to TV in 2005, two of the writers chosen were Paul Cornell and Mark Gatiss, both of whom had been regular contributors to the book line from almost the start.

But there were more interesting influences as well. One of the things we’ll be charting over the second half of these essays is the way that some ideas keep popping up in different forms.

This requires us to take a rather different attitude to these later stories. With the earlier stories, we’ve been looking at them in the context of the time, pretty much, tracing ideas through a linear path. But we’re about to hit a tangle — for much of the next few years there isn’t a single, definitive Doctor Who, but a whole bunch of mutually contradictory, but mutually-reflecting, continuities. You can’t trace an idea from story A to B to C, but rather note how story C takes elements of both story B (which is written as a deliberate attack on story A because of something A’s writer once said to B’s at a convention) and story X (from a different range, whose editors have licenses to different characters than B’s does) and combines them.

It’s only really when the TV show returns in 2005 that a singular narrative is imposed on Doctor Who again (and one of the reasons I lean quite strongly toward the “not a fan of the new stuff” side is that I don’t like singular narratives being imposed rather than prismatic ones). The effect is rather like the way that, after a mass extinction (in this case the extinction of the TV programme), very quickly whole new ecological niches will open up and biodiversity will increase rapidly, before (as in this case) a new apex predator (the new series) comes along and causes another wave of extinctions.

But this means that what looks ‘important’ now is very different to what looked ‘important’ at the time.

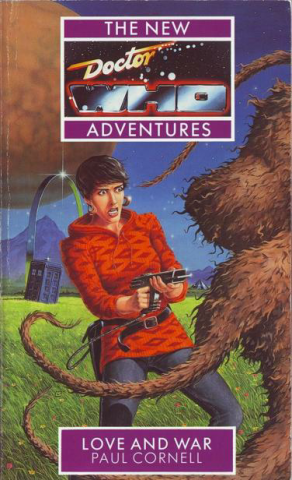

When it came out, Paul Cornell’s second Doctor Who novel, Love And War, was mostly notable for two things. The first was the temporary departure of Ace, and the second was that, as Philip Sandifer points out, it pushed the idea of the dark, manipulative Doctor as far as it could possibly go. Reading Ace’s departure, it’s easy to see just how different this was from the TV show that had finished only three years earlier:

She looked between the two of them.

‘Fake Mum and Dad!’ she spat. ‘Bit worse, though. Thanks, but no thanks!’ She stood up. ‘Were we ever mates?’

‘Yes!’ the Doctor shouted, his voice like that of an aggrieved little boy.

‘We can’t have been.’ Ace took a few steps away. ‘You’re not human, right, Professor? You’re so clever, you little shit.’ A few more, confident, steps backward. She took the cube from her pocket, and tossed it from hand to hand. ‘I’m never gonna play your games again . . . never get manipulated again. Know what? You can have this too!’

Ace grabbed the jacket off her shoulders and slammed it on to the ground. Then she walked quickly away, clutching the cube to her chest.

Some way off, Máire met her and put an arm around her shoulders. The two women vanished into the depths of the forest. They seemed to be trying to speak to each other, as if Ace was having trouble understanding Máire’s language. Just before she was gone, Benny thought that Ace had taken a quick glance over her shoulder.

But she couldn’t be sure.

Benny wandered over to the jacket, and picked it up. ‘Do you think she’ll ever need this again?’ she asked the Doctor.

‘Oh yes . . .’ the Time Lord muttered, gazing after his lost companion. ‘But it doesn’t make it any better.’

That is clearly, for 1992, the most important aspect of this novel.

For 2013, the most important aspect is Bernice Summerfield.

In part, this is because the character — the first new companion to be created for the novels — took on rather more of a life of her own than anyone expected. Not only did she regularly appear in the novels, when Virgin lost their license to Doctor Who, they kept publishing the New Adventures with Bernice as the lead character. Big Finish later took over the character, and to this day she still has not only her own novel series but her own series of audio dramas, as well as making occasional appearances in Big Finish’s Doctor Who stories. She’s so popular she has two separate TV Tropes pages.

But mostly it’s because…well…Bernice Summerfield is a time-travelling professor of archaeology (though she didn’t exactly come by the title honestly) who travelled with multiple incarnations of the Doctor and is strongly hinted to have had a sexual relationship with at least one of them…

While the character of River Song (a companion between 2009 and at least 2013, who appeared in the most recent episode broadcast as I write this) is very different in many ways from Bernice Summerfield, she does seem to have been taken as the starting point — the two characters diverge, but the River of Silence In The Library (2009) is very like Bernice.

In truth, Bernice Summerfield seems to be a character who is more popular with writers than readers — she’s pretty much universally beloved among the writers who’ve written for her, but seems more than a little irritating. The description of her as “a combination of the two Joneses, Indiana and Bridget” pretty much sums it up, and to my mind not in a good way. Yet most of the best writers who have done Doctor Who work have contributed stories to her various ranges, and we’ll be seeing more than one story from the Benny (as her fans call her) ranges as we go along.

She’s the first character — in many ways the first idea — from the New Adventures to become a proper, accepted part of Doctor Who, and to affect the future course of the show. There would be others.

So as 1992 drew to a close, the books were firmly established as a proper continuation of the TV show, with a new companion, and some actual character development. But 1993 was the thirtieth anniversary. Surely, surely, the books must just be a temporary thing, and the TV show must be coming back? Maybe even with a multi-Doctor special?…

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.