Future Crimes

April 4th, 2013

OR: last year I went to the movies and all I got was a sense of temporal displacement!

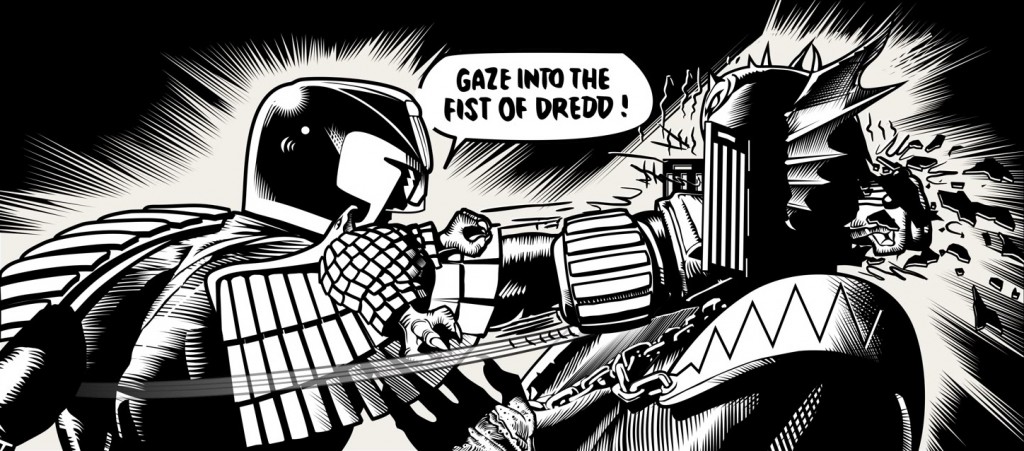

DREDD, dir. Peter Travis, 2012

This relatively low-budget attempt to graft a late seventies vision of the future onto the present day doesn’t quite come off seamlessly – the opening drone-cam riot shots would be much more convincing without the sci-fi data overlay – but the grim lack of distance between these three (equally imaginary?) time zones ensure that this bolted-together aesthetic is effective rather than ridiculous in the end. A lot of the credit here has to go to Karl Urban, who sets the tone of the movie by somehow managing to play the perma-frowning Dredd with a straight face:

Like Urban’s Joe Dredd, DREDD (the movie) treats exposition as little more than a series of snappy situation updates, necessary only because they point the way from one dynamic lesson in pain compliance to another. The result is a lean, efficient action films that you suspect the Judge himself would approve of. The rules are established in the opening scene and are ruthlessly enforced throughout: you get a quick report of the location and nature of the crime in progress (the irradiated ruins of a future America; whatever takes your fancy) then whooosh, before you can say “hot shot” the situation has been resolved with the maximum amount of acceptable violence.

Because hey, when you fuck up, he’s got to fuck you up, right?

Right.

There are obvious affinities here – with Robocop, say, or with your Carpenter movie of choice – but these reference points never threaten to overwhelm the movie. Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury’s almost/alternate score Drokk is far more heavily indebted to Carpenter’s work, for example, and while the soundtrack that plays out in its place is less immediately striking it’s also perhaps better suited to DREDD’s relentless utilitarian drive. The aesthetics of past, present and future might me all jumbled up here, but there’s no time for reverence in this movie – everything is judged by how well it performs in its specific moment in the field.

Still, I’d be remiss in my duties as a reviewer if I didn’t point out that there are certain plot similarities to Batman Incorporated vol 2, #6, and while I don’t know how Peter Travis and Alex Garland were able to travel through in time in order to rip that script off, I’m glad that they did all the same – this is a joke about the seemingly manditory you comparisons with The Raid, you can tell it’s a good gag because I feel the need to flag it up like this. Since we’re all pals here I’ll assume that we can all agree that the similarities between DREDD and The Raid are worth talking about – in the same way that its resonances with this Moebius strip are worth talking about – but that simply saying “The Raid” is in no way the end of the conversation. There are many different ingredients in DREDD, and the end result might have familial similarities with various other movies, but it’s overwhelming flavour is still undeniably that of “Judge Dredd”.

As my good pal (the devil)Andre Whickey has pointed out, there are several different types of Judge Dredd story, and this is a great example of one of them – Judge Dredd as straight action story. While this means that DREDD can’t touch 2012’s Day of Chaos story (for example) for either political complexity or gonzo fanboy thrillpower, it does mean that this is Judge Dredd at its most insidious, a compelling story of good guys vs. bad guys that doubles as a cheap, spooky reminder of the fact that authoritarianism can always be made to look both necessary and cool using the right tools:

LOOPER, or “Blunderbuss as Metaphor”, dir. Rian Johnson, 2012

I meant to write about this while it was still playing at a theater near you, but perpetual fuck-up that I am I never got round to it. Thankfully it would seem that it’s currently scientifically possible to revisit the cinematic experience by applying 650 nm lasers to a rotating disc (he means it’s available on DVD now – Ed), so my observations have been rendered freshly relevant, always and forever.

The theme of recurrence is every bit as crucial to Looper as its title suggests it should be – when Jeff Daniels’ crime boss isn’t lecturing suave young “Looper” Jo)e(seph Gordon-Levitt) about why he should ditch his dream of living in France (“I’m from the future, go to China”), or delivering Austin Powers-style asides about why you shouldn’t worry about the mechanics of time travel, he’s bemoaning the lack of originality in the world. Noting that Joe has dolled himself up like something from an old movie, Daniels’ character asks why he doesn’t do something new. This question is posed implicitly by the aesthetic of the film, which starts out as a sci-fi story in film noir dressing soon blurs into a Twilight Zone episode set in the Blood Harvest campaign from Left 4 Dead. That writer/director Rian Johnston manages to bring these two stories together in a finale that exposes their limitations is key to Looper’s success: this isn’t a startlingly new film, despite Shane Carruth’s involvement, but it’s unmistakably the product of people who are smart and ambitious enough to point towards something that is just out of their reach.

If you want a plot summary, there’s always wikipedia; if you want to stress about the details of the plot (like, for really reals, does the future that Bruce Willis comes from exist, and if so, what’s the story with the Bruce Willis he killed while he was JGL?), that’s what the rest of the internet is for. Personally, I’m more interested in the progress of Joe)(seph Gordon-Levitt) from desperately numb minor player to bleary-eyed viewpoint character to active moral agent. JGL squints and glowers his way through the prosthetics and into the second-best Bruce Willis performance of 2012 – narrowly beating Bruce Willis’s performance as himself in Looper only to be trumped by Willis’ unexpectedly tender turn in Moonrise Kingdom. As both the horror and time travel plots collapse into mutual-unsustainability, it’s Gordon-Levitt who sells us on the exhausted tragedy of the set-up. Clothed in the past, scrabbling to cut short his own future, all in the name of an exhausted present – looking at JGL’s face as he gets a glimpse of the world beyond the range of his blunderbuss for the first time, you definitely feel the need for something new. That Joe chooses to envision a better world by – uh, *SPOILERS* I guess – removing himself from the equation is the one radical detail that makes the movie. Flying in the face of our present orthodoxy – in which our current continuum must be maintained, no matter what the cost – Looper comes close to its goal of presenting something new in its final few minutes.

At the end, Emily Blunt’s left on her own with a stock creepy child. It’s not entirely clear whether she’s going to be able to help him grow into an actual human being, but having been liberated from the shackles of story she’s finally free to try.

THE MASTER, dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012

Despite eschewing the futuristic trappings of Dredd and Looper in favour of that other improbable destination, the past, The Master is still the best movie about time travel to have been released in 2012. The fact that it’s all about the impossibility of time travel only makes it crueler – apparently you really can’t step into the same river twice, and no amount of Serious Acting can force the past to tidy up after itself.

Paul Thomas Anderson is no stranger to difficult narrative structures or showcase performances, but where his previous films have always built to some form of catharsis – be it in the form of Biblical plagues or bowling alley beat downs – the two impossible forces in The Master pass each other by in the end, their trajectories forever changed but un-halted.

Joaquin Phoenix’s alcoholic veteran Freddie Quell and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s affably bombastic cult leader Lancaster Dodd share a determination to make something out of the mess of memory that life has written all over them. Phoenix plays Quell with a chronic hunch that might seem like grotesque Oscar-bait if he didn’t hold it with a conviction that suggested that he’s seconds away from crumpling out of existence altogether under the weight of gross psychological pressures. Hoffman’s Dodd, meanwhile, has a ruddy drinker’s face that seems to contain every bit as much grain as the vast, post-war landscape that Anderson details so lovingly:

Anderson maintains the same clarity of purpose while capturing the interactions between his two leads – the camera stays close in on their individual faces, drawn to explore their depths while still keeping a methodical head about it, always mindful of the need to change focus, to pull back to take in the wider scene. The end result is a massively ambitious, uneasy film, one that renders the raw excitement of these American dreamers unforgetable while also letting their folly, fallibility and sheer rage and hucksterism shine through. Whatever the man might tell you, you can never go back: if the past exists at all it does so only as recorded in our land and our bodies, and trust me, that mess is *never* going to be what it was again.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.